Canada is entering a new era of climate risk, where homeowners, insurers, and governments are being pushed beyond what the old risk-sharing system was designed to handle. In the past decade alone, climate-related disasters have significantly cut into insurers’ margins and created gaps that public disaster-assistance programs are being forced to fill.

Why Canada’s Property Insurance System is Under Strain

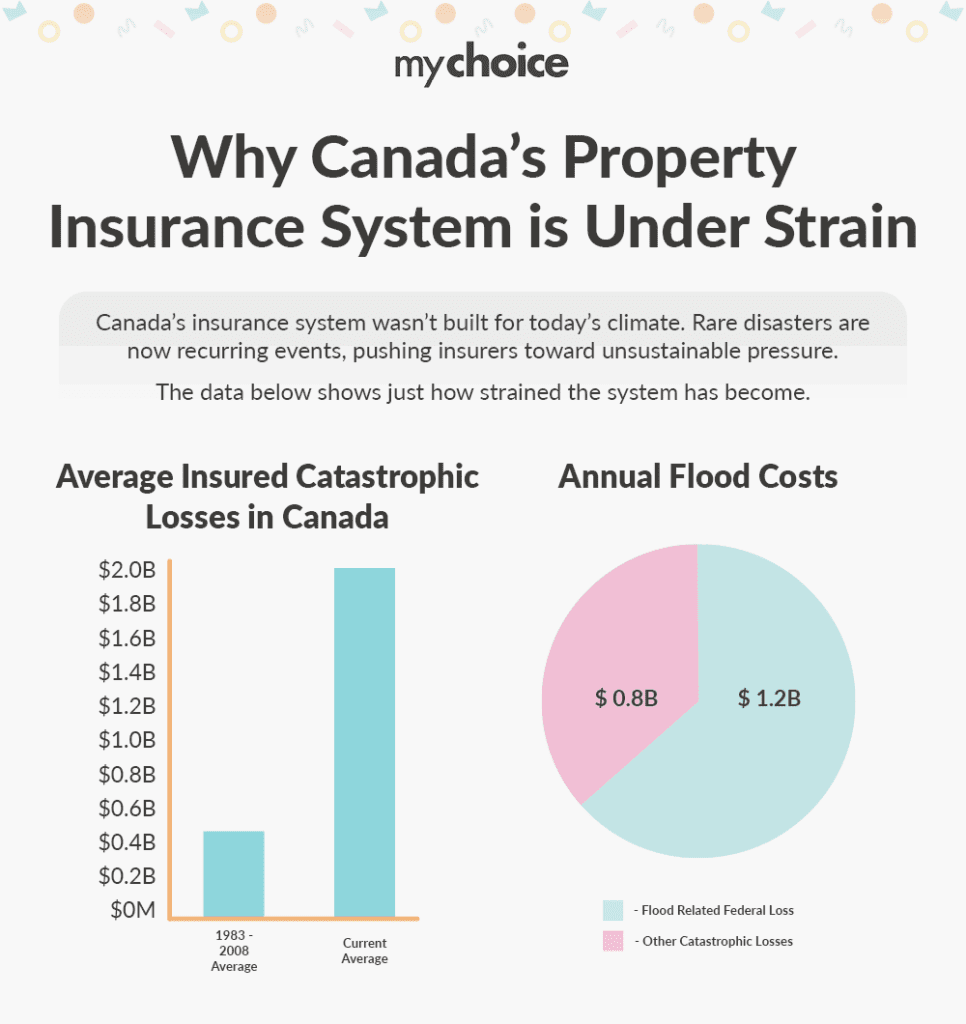

Disasters that were once considered “once in a century” events now occur every few years. This means that insurance companies and reinsurers are not only paying out more, but also more often. A quick look at the national picture shows why the system is under pressure:

- According to Catastrophe Indices and Quantification (CatIQ), average insured catastrophic losses in Canada exceed $2 billion annually. For comparison, between 1983 and 2008, Canadian insurers averaged only $422 million in severe weather-related losses per year.

- 2023’s wildfire season recorded Canada’s largest burn area in history. According to the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System, over 15 million hectares were burned.

- Floods alone, according to the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), are expected to cost the federal government $1.2 billion per year.

Why Risk Keeps Getting More Expensive

Climate change is reshaping the entire economic landscape around risk, and clearly, the physical damage from extreme weather is growing faster than our systems were designed to handle. Three leading national organizations help explain why the costs keep rising:

When Insurance Pulls Back, Taxpayers Step In

There’s a limit to what private insurance markets can sustainably cover. Once losses exceed that limit due to increased claims from events such as flooding, fires, and hurricanes, the government must step in with Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA).

The DFAA effectively serves as the government’s insurance deductible for provinces, kicking in when disasters exceed certain per-capita cost thresholds. But as disasters grow more severe, that federal role expands, making taxpayers the “reinsurer of last resort.” That’s why Canadians end up paying for climate disasters twice:

- Through their home insurance premiums, which continue to rise as insurers absorb more risk.

- Through their taxes, which fund federal and provincial recovery efforts when private coverage hits its limits.

According to the PBO, the federal government is now paying dramatically more for disaster recovery than at any time in its history. DFAA spending averaged $881 million per year from 2010 to 2024. Over the next decade, that figure is projected to double to $1.8 billion per year.

Recent events have already triggered massive spending:

- BC’s 2021 floods destroyed highways, farms, bridges, and entire communities, requiring billions in federal and provincial recovery funding.

- Alberta’s 2016 and 2023 wildfires resulted in significant public expenditures for evacuations, temporary housing, reconstruction, and community support.

- Quebec and Atlantic Canada have experienced repeated federal payouts for severe storms, freezing rain, and coastal flooding, many of which fall outside private insurance coverage.

In each case, private insurers covered only part of the damage. Without meaningful reform, public budgets will continue absorbing a growing share of climate-related losses.

International Models: What Canada Can Learn

Other climate-exposed countries have already built hybrid public-private insurance solutions. These are options that may be worth exploring in Canada:

What a Canadian Public-Private Risk Pool Could Look Like

A smarter, modernized public-private risk pool would protect homeowners, stabilize premiums, and reduce federal disaster-relief bills. A Canadian model could include these features:

- A national wildfire insurance pool: This would spread wildfire risk nationwide rather than leaving vulnerable regions to bear the costs alone. This would keep insurance available and affordable in areas where private companies might otherwise restrict coverage or raise premiums after major fires.

- A flood reinsurance layer: As Canada develops its National Flood Insurance Program, a federal reinsurance layer could sit on top of private coverage. It could be used to absorb the largest, most unpredictable losses, protecting insurers from insolvency and ensuring families can still obtain coverage.

- Risk-based premiums balanced by a government backstop: Premiums would be based on actual local risk, so safer homes pay less and high-risk homes pay more, but without becoming unaffordable. A government backstop would cap premium increases, preventing Canadians from being priced out.

- Mandatory adaptation credits: When a home is rebuilt or significantly renovated, homeowners would receive financial credits or premium discounts for climate-resilient upgrades, such as fire-resistant siding or basement flood protection. This ensures upgrades actually happen and reduces damage.

- Building-code-driven resilience upgrades: Updated building codes could require protective measures in high-risk regions, such as ember-resistant vents in wildfire zones. These upgrades reduce losses, meaning fewer taxpayer-funded disaster payouts and more homes that can withstand the next major event.

MyChoice CEO Aren Mirzaian observes, “Climate risk is outpacing the insurance system’s ability to absorb it. When losses rise faster than mitigation, insurers inevitably pull back — and the cost doesn’t disappear. It shifts onto taxpayers through disaster relief and recovery programs. Canada needs a national resilience strategy that strengthens adaptation, modernizes risk sharing, and ensures that families aren’t left paying for climate change twice — once through their premiums, and again through their taxes.”

Key Advice from MyChoice

- Install backflow valves, sump pumps, and fire-resistant materials, especially if you live in disaster-prone areas. Adapting these safety measures reduces both damage and premiums.

- Ask your insurer about wildfire, hail, and storm-resistant upgrades that qualify for discounts.

- If you live in a flood-prone area, add overland flood coverage. Note that standard home insurance does not include flood protection.