Your local community can change your life expectancy by as much as 14 years and affect how long you live in good health. This gap isn’t just a public health issue; it’s a financial one. Fewer healthy years often mean earlier health complications, reduced earning power, and greater financial strain on families. All these factors directly affect when life insurance should be purchased, how much coverage is needed, and which additional protections (such as critical illness or disability insurance) become essential.

Our Methodology

To understand how health varies across Canadian municipalities, our team at MyChoice looked at the most recent Statistics Canada dataset on life expectancy and health-adjusted life expectancy. The dataset included:

- Life expectancy (LE): How long a newborn can expect to live

- Health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE): How many of those years are likely to be lived in good health

- Share of life in good health: HALE divided by LE

Our team then took the following steps to understand the data:

- We analyzed the full range of life expectancy results. We examined the national spread between the highest and lowest municipal life expectancies to assess the extent to which health outcomes vary across Canada.

- We reviewed national patterns in healthy life expectancy. HALE results reveal the number of years Canadians spend in good health, not just how long they live. We compared HALE and total life expectancy to identify where the largest “healthy life” gaps occur.

- We interpreted how LE and HALE interact. By looking at the difference between total lifespan and healthy years, we identified broad patterns in where Canadians tend to experience earlier declines in health.

- We examined how demographic factors shape longevity. We reviewed how factors such as education, income, population size, and population density correlate with LE and HALE. This helped us understand why certain regions of Canada experience better or worse health outcomes.

- We identified which large cities sit near the national median. Using examples from the study, we highlighted major urban centres that are close to the national midpoint for both LE and HALE, providing Canadians with familiar reference points.

By combining the study’s modelling with our own analysis, we can provide Canadians with a clearer picture of how their community fits within the national health landscape and what these differences might mean for long-term well-being, financial planning, and life insurance needs.

Where Major Canadian Cities Sit on the Life Expectancy Curve

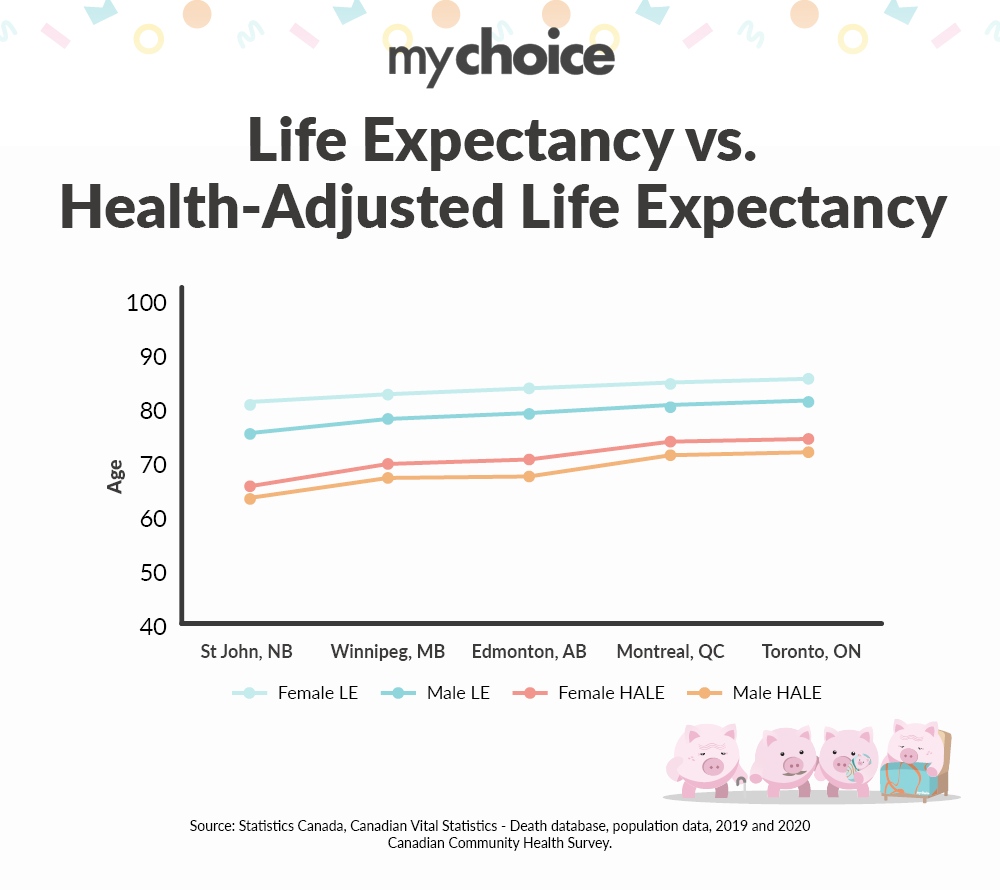

The StatCan study examined 1,227 municipalities across Canada and found that life expectancy (LE) and health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) vary dramatically from one community to another. The infographic below highlights the relative positions of major Canadian cities.

There is a clear gap between the average life expectancy and the average life expectancy in good health across several major cities. While total life expectancy (LE) rises steadily from smaller centres such as Saint John to larger cities such as Toronto and Montreal, health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE) consistently lags by 10 to 15 years for both men and women.

Why is This Important for Life Insurance

Life insurance companies do not price policies solely based on age. They assign applicants to health categories that reflect underlying risk, such as “excellent,” “good,” or “average” health. Moving from one category to the next can meaningfully increase premiums, even when age stays the same.

MyChoice data shows that for a typical Canadian applying for term life insurance, monthly premiums can rise by 30% to more than 100% as health classifications worsen over time. In practical terms, Canadians living in communities with fewer healthy years are more likely to apply for coverage later in life, or after early health issues emerge, which can push them into higher-cost categories or limit available options altogether.

This is why timing matters as much as coverage amount. Securing life insurance while still in good health can lock in lower rates for decades, helping families protect their financial stability even as health risks increase later in life.

“Canadians should be looking not just at how long they’re expected to live, but how many years they’re expected to live in good health. Municipal health gaps of 10 to 14 years fundamentally change the financial risks families face. This is exactly where life insurance becomes a stabilizer, especially in regions with lower healthy life expectancy,” says MyChoice’s CEO, Aren Mirzaian, commenting on the findings of the article.

What The Data Reveals About Major Cities

What’s most striking about the study is not where individual cities fall, but the wide gap between municipalities at opposite ends of the spectrum. The study found differences of approximately 12.5 to 13 years in life expectancy between municipalities at the 5th and 95th percentiles, and 13 to 14 years in health-adjusted life expectancy across the same range.

These gaps are larger than the differences between most Canadian provinces. In other words, the municipality you live in matters more than your province when it comes to predicting how long you’ll live and how many of those years will be healthy.

- Toronto appears near the higher end of the life expectancy range for both women and men, suggesting that Canada’s largest city offers relatively strong health outcomes compared to the national municipal average.

- Montreal and Quebec City also cluster at the higher end, indicating that major Quebec urban centres provide health advantages comparable to those of other large Canadian cities.

- Edmonton and Hamilton represent the national median for women’s life expectancy, making them typical examples of what most Canadian women can expect in terms of longevity.

- Winnipeg falls near the median for men, ranking in the middle of Canadian municipalities.

- Saint John, New Brunswick, appears in the lower-to-middle range, reflecting some of the challenges faced by smaller cities and those in provinces with older populations and economic restructuring.

Education Is the Strongest Predictor of Living Longer

The StatCan study found that the higher the proportion of residents in a municipality with postsecondary education, the longer and healthier residents tend to live. The tables below use something called “correlation coefficients”. These are statistical measures that indicate how strongly two variables are related. Here’s how to read them:

- Positive numbers (such as 0.24) indicate that the two factors move together. For example, as the percentage of people with postsecondary education increases, life expectancy tends to rise.

- Negative numbers (such as -0.04) indicate movement in opposite directions. When one increases, the other tends to decrease.

Numbers closer to 1 or -1 indicate a stronger relationship; numbers closer to 0 indicate a weaker relationship. An asterisk (*) indicates that the relationship is statistically significant and not merely a chance finding in the data.

Think of it this way: a correlation of 0.24 doesn’t mean education causes a 0.24-year increase in life expectancy. Instead, it means that municipalities with higher levels of education consistently exhibit longer life expectancy across Canada’s 1,227 communities studied.

Correlation with Life Expectancy (LE) at Birth

| Municipal Characteristic | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| % with Postsecondary Education | 0.24* | 0.27* |

| Population Size | 0.12* | 0.12* |

| Average After-Tax Income | 0.11* | 0.11* |

| Population Density | –0.04 | –0.04* |

This means that in municipalities where a higher percentage of residents aged 25-64 have postsecondary education, women live longer by a measurable, consistent margin. This relationship is even stronger for men (0.27 vs. 0.24). Meanwhile, population size and income show weaker positive relationships, and population density barely matters at all, meaning living in a dense city doesn’t inherently shorten or lengthen your life.

Correlation with Healthy Life Expectancy (HALE) at Birth

| Municipal Characteristic | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| % with Postsecondary Education | 0.35* | 0.36* |

| Population Size | 0.10* | 0.11* |

| Income | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Population Density | 0.01 | 0.01 |

Education’s impact is even stronger when we consider healthy years of life rather than total years. Municipalities with higher levels of education have residents who live longer and spend significantly more of their lives in good health.

Correlation with % of Life Spent in Good Health

| Municipal Characteristic | Women (τ) | Men (τ) |

|---|---|---|

| % with Postsecondary Education | 0.32* | 0.34* |

| Population Density | 0.06* | 0.10* |

| Income | –0.07* | –0.07* |

| Population Size | –0.02 | 0.00 |

Here’s where things get interesting: education remains the strongest positive predictor of living more years in good health. But notice that income shows a negative correlation. This doesn’t mean money makes you unhealthy. However, it suggests that wealthier municipalities may have older populations who live longer but accumulate more years of chronic conditions. Population size also shows no meaningful relationship, reinforcing that larger populations are not necessarily better for health outcomes.

Men Face Larger Health Inequality Than Women

Across municipalities, the life expectancy gap between the 5th and 95th percentiles is approximately 12.5 years for women, compared with approximately 13.9 years for men. The healthy life expectancy gap is also larger for men, reaching nearly 14 years. This means men are more affected by regional differences and more vulnerable to local socioeconomic and environmental conditions.

Researchers suggest several possible reasons: for instance, men still dominate occupations with higher physical risk, and male health behaviours like smoking, delayed medical care, and substance use show more variation across regions. Economic shocks and unemployment also tend to affect men’s longevity more dramatically.

What These Health Gaps Mean for Life Insurance

When examining the municipal health gap, the implications for life insurance are significant. While life insurance isn’t priced by municipality, the underlying health factors insurers assess, such as chronic disease and mental health conditions, are strongly influenced by local conditions.

Here’s what these findings tell us:

Key Advice from MyChoice

- Consider life insurance sooner rather than later. Coverage is most affordable before health issues appear.

- Pair life insurance with critical illness and disability insurance to protect against lost income during years when health problems are more likely.

- Municipalities with better access to clinics, mental health support, and preventive care tend to see longer, healthier lives. If your area lacks services, look for provincial or virtual options.